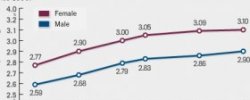

Poland’s gains in mathematics and science on the 2012 PISA assessments made big news in the United States. The impressive achievements by fifteen-year-old Polish youngsters contrast starkly with the scores of American youngsters. U.S. results have remained essentially flat since the tests were first given in 2000 to 180, 000 students in 32 countries. As a result of these diverging trajectories, Polish students now outperform their American peers in both math and science by a significant margin.

I was a high-school teacher in Poland in 1990–91 and again in 1994–95. During my first stint, I taught in a town of about 15, 000; the second time, I worked in one of Warsaw’s elite high schools. The children of the students I taught are now the Polish generation that is outpacing much of the world in academic achievement.

After reading the new PISA report—especially when read in tandem with Amanda Ripley’s excellent recent book—I am not really surprised by Poland’s success. The students I taught had many of the attributes for success that now benefit their own children. These included families that care deeply about education and that view education to be the path to upward mobility. By doing well in school, children could do more with their lives. This was a belief I saw in the parents both of small-town students and of elite metropolitan kids.

Poles also take great pride in knowledge: acquiring it and showing it off. I was always amazed, and more than slightly embarrassed, by how much more Poles knew about American and English literature, the history of mathematics and how to use math (Poland is the home of Copernicus), and science (especially the natural sciences) than I did. I spent hours with Polish families and students in the forest, hunting mushrooms, talking about the wildlife we saw, and being asked what this tree or that plant was called in English.

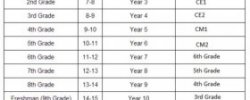

Liceum ogólnokształcące [liˈt͡sɛum ɔˌɡulnɔkʂtau̯ˈt͡sɔnt͡sɛ] is an academic high school in the Polish educational system. They are attended by those who plan to further their academic education (i.e. attend university).

Liceum ogólnokształcące [liˈt͡sɛum ɔˌɡulnɔkʂtau̯ˈt͡sɔnt͡sɛ] is an academic high school in the Polish educational system. They are attended by those who plan to further their academic education (i.e. attend university).