It is extremely good news to hear that the United Republic of Tanzania has cancelled school fees at the secondary level. This new policy aims to free families from any fees and contributions to education for 11 years of schooling. It is in line with the new commitments made by countries as part of the sustainable development agenda, and, as detailed in the latest GMR 2015, is a key policy for encouraging universal primary and secondary education. As this blog warns, however, abolishing fees is not an end in itself. Indirect costs must be monitored as well to ensure they don’t increase to make up for the change.

It is extremely good news to hear that the United Republic of Tanzania has cancelled school fees at the secondary level. This new policy aims to free families from any fees and contributions to education for 11 years of schooling. It is in line with the new commitments made by countries as part of the sustainable development agenda, and, as detailed in the latest GMR 2015, is a key policy for encouraging universal primary and secondary education. As this blog warns, however, abolishing fees is not an end in itself. Indirect costs must be monitored as well to ensure they don’t increase to make up for the change.

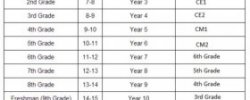

Many countries have already expanded basic education to include lower secondary. Before Tanzania’s announcement, analysis of documents in the UNESCO Right to Education Database outlined in the GMR 2015 showed that 94 out of the 107 low and middle income countries have legislated free lower secondary education. Of these, 66 have constitutional guarantees and 28 enacted other legal measures. As of today, only a few nations charge lower secondary school fees, including Botswana, Guinea, Papua New Guinea and South Africa.

Tanzania joins the long list of countries which have made lower secondary education compulsory as well. Two out of three countries where lower secondary education was not compulsory in 2000 had changed their legislation by 2012. Among those countries that legislated compulsory attendance in lower secondary education since 2000 were India, Indonesia, Nigeria and Pakistan. As of 2012, only 25 countries have no legal requirement for lower secondary attendance, including Iraq, Malaysia and Nicaragua.

Fee abolition at the primary increased the likelihood that students enrolled in school, as Tanzania will have seen from its own history since 2002. The same was true for Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Uganda. Fee abolition in 2005 in Burundi was associated with a sharp reduction in the percentage of children of primary school age that had never been to school.

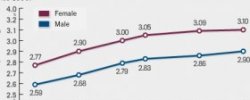

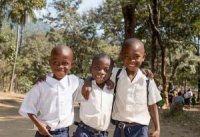

Tanzania should also be encouraged by the positive equity impact of eliminating school fees. Kenya, Malawi, Timor-Leste, Uganda and Zambia eliminated school fees at the primary level which resulted in an increase in the enrolment of disadvantaged groups. Uganda, Tanzania’s neighbor, saw particularly positive results: studies found that fee abolition for primary education reduced delayed entry into schooling, incentivized enrolment and reduced dropout, particularly for girls and for children in rural areas

Why the increased demand for secondary schooling? Among the most significant factors behind the increased demand for secondary schooling is the rising rate of students completing primary education, which results in more students being eligible for continued study. In Thailand, achieving compulsory universal primary education eventually led to increased pressure on the government to expand access to lower secondary school as well.

Why the increased demand for secondary schooling? Among the most significant factors behind the increased demand for secondary schooling is the rising rate of students completing primary education, which results in more students being eligible for continued study. In Thailand, achieving compulsory universal primary education eventually led to increased pressure on the government to expand access to lower secondary school as well.

Nothing comes for free: However, as seen with the fee abolition trend at the primary level, even when school is made free, families can still pay significant amounts for their children’s education. It has been shown that providing school uniforms decreases dropout, reduces absenteeism and encourages grade progression, for instance. This is why the GMR 2015 called for education to be truly free, so that indirect financial burdens on households such as transport, examination papers, school lunch and extra tuition were also taken into account.

Governments must offset the funds previously provided by school fees. When a decision is made to abolish fees, countries must offset the need for funds at the school level. Previous experience indicates that capitation grants provided to offset these needs at the primary level, for instance, were often insufficient, poorly delivered and inadequately targeted. The grants were usually lower than what schools in most sub-Saharan African countries had collected from parents, forcing them to manage more students with fewer resources. In most countries, grants were not indexed to inflation, and lost significant value in real terms over time. In Sierra Leone, for instance, the subsidy amount of US$2.20 per student per year was set in 2010 and even then deemed too low to cover schools’ regular operating costs. This and payment delays led to reinstituting school fees. In addition, recent research from Lesotho indicates that the per capita allocation per pupil was not appropriate as it did not account for schools’ differing needs.

Delivery of these grants to offset costs has been at times inadequate in some countries as well. In India, it was found that funds were not allocated on time because of banking delays, and did not always reach primary schools. In South Africa, a no-fee policy targeted to the poorest primary schools was expanded to cover 60% of schools in 2008 and 2009. But significant implementation lags left many poor households still paying fees and the frequency of nonattendance attributable to school fees increased. Another substantial problem seen at the primary level is well-documented corruption in capitation grant programmes, including in Kenya and Uganda.